Gut Health

A brief guide to a lengthy process – your digestive system explained

AUTHOR:

Molly Warner, Gastrointestinal and Intuitive Eating Dietitian

The gut, or more formally named the gastrointestinal tract is an 8-9m long tube from the mouth to the anus. This means the gut is our main interaction with the environment! One major function of the gut is to digest (breakdown) food and absorb nutrients.

The gut also has a large influence on our immune system; in fact, about 80% of our immune system lies in the gut! A lot of this has to do with the gut microbiome (see our article for more on this).

We also have a ‘second brain’ in the gut, called the enteric nervous system. The nerves carry messages into and away from the gut (see our article for more on this).

Back to the lengthy tube now. Let’s say we are a delicious nut bar, about to take a journey through the GI tract… Here we go!

First, we start in the mouth. We are hit with saliva, a liquid full of enzymes, electrolytes, mucus, hormones and antimicrobial compounds. Salivary glands produce about 1 litre of saliva every day – now that the food has entered, they are stimulated to secrete the intricate liquid right away. The teeth masticate (chew) the sticky nut bar to mechanically digest or literally ‘breakdown’ the tough snack. This is important! Without saliva or mastication, the journey becomes a rough one.

The next part is turbulent. About 50 pairs of muscles contract in a very rehearsed manner to swallow the lumpy slobbery nutty mess. A quick passage through the oesophagus will take us into the stomach, passing a gate called the lower oesophageal sphincter. If this gate doesn’t open and shut as it’s supposed to, reflux might occur.

The stomach holds acid that kills unwanted bacteria that might have come through with the slobbery nut bolus – it’s a protective mechanism. The stomach is also strong; it’s thick muscular walls contract to break up the food bolus and mix it with stomach acid, saliva, liquids. We might spend up to 4 hours here. By the time we are finished, we are no longer ‘food’ or a slobbery-nutty-mess, but more a semi-fluid paste called chyme.

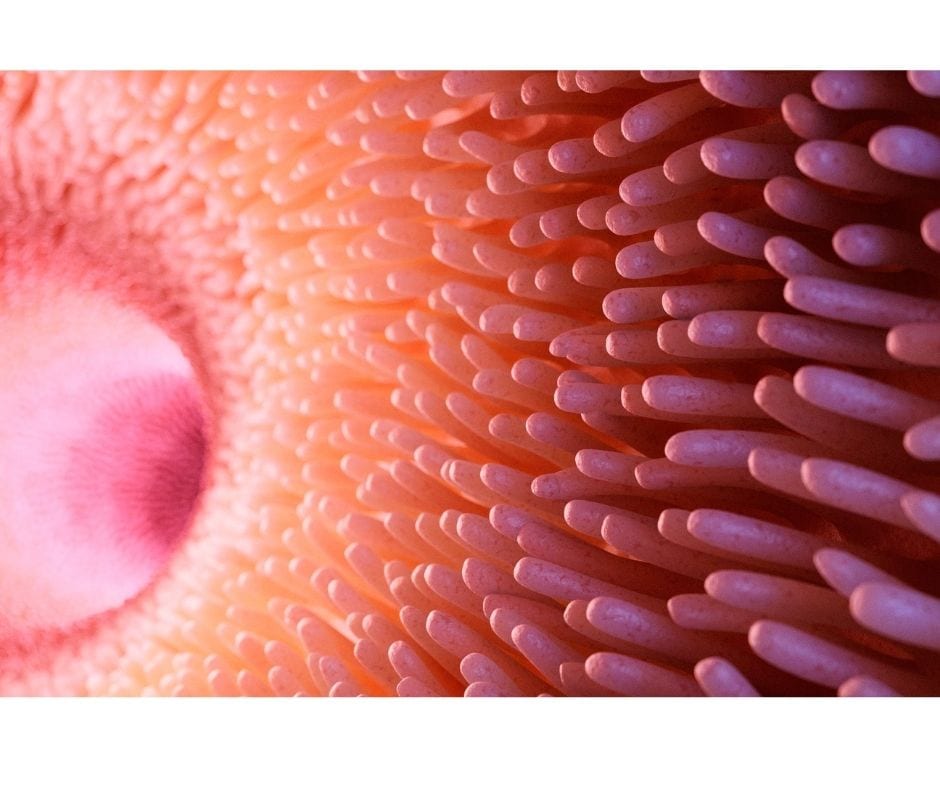

Moving on! Chyme enters the small intestine – the longest part of the gut, about 5 metres. The walls of the intestine are folded up into finger-like projections (villi), which are folded into smaller folds (microvilli) to create the largest possible surface area for absorbing nutrients from the gut and into the bloodstream. If the entire small intestine was stretched out it would cover half a badminton court! If we stretched out our skin, it would only cover a small dining table.

The small intestine receives lovely bile juices from the liver and gallbladder, and helpful enzymes from the pancreas. Together the bile and the enzymes breakdown nutrients into their smallest parts. Vitamins, minerals, sugars, fatty acids and amino acids are absorbed (moved) from the small intestine into the blood stream. We don’t have the tools (enzymes) in the small intestine to breakdown fibre – so let’s keep with the fibre from our nut bar and continue on our way.

The contents of the intestine are pushed along as the muscular intestinal wall contracts in a sweeping motion, called peristalsis. This occurs in response to stretch – when we eat, we stimulate these contractions in order to shuffle everything along. The small intestine reaches the large intestine on the lower right side of the abdomen.

The large intestine (aka colon) has segments that move upwards (ascending colon), across the abdomen from right to left (transverse colon), down the left side of the abdomen (descending colon) and towards the back passage (sigmoid colon) to the rectum, where it is stored until the time is right and the anus gives the ‘go ahead’.

The anus really is special. There are sophisticated sphincters that work as a team to let us know if the matter (gas or faecal matter) is appropriate to pass. The sphincters communicate with each other to allow defecation (pooing) usually between once every other day and up to 3 times a day. Then, release! (More on poo here, if you’re that way inclined).

Well, that was a journey… 8 or 9 metres, 12 to 48 hours, a whole lot of twists and turns, we got mashed up, hit with acid and juices, broken down and mushed together again. There were characters and stories we didn’t have time to tell in this brief introduction – speak to our dietitians if you’re keen to learn more about your amazing digestive system and its function. We love it!